Anxiety From Reactions to Covid-19 Will Destroy At Least Seven Times More Years of Life Than Can Be Saved by Lockdowns

By Andrew Glen, Ph.D. and James D. Agresti

May 4, 2020

Medical studies show that excessive stress and anxiety are among the most debilitating and deadly of all health hazards in the world. Beyond their obvious effects like suicide and substance abuse—these mental stressors are strongly related to and may trigger and inflame a host of ailments like high blood pressure, digestive disorders, heart conditions, infectious diseases, cancer, and pregnancy complications.

Based on a broad array of scientific data, Just Facts has computed that the anxiety created by reactions to Covid-19—such as stay-at-home orders, business shutdowns, media exaggerations, and legitimate concerns about the virus—will destroy at least seven times more years of human life than can possibly be saved by lockdowns to control the spread of the disease. This figure is a bare minimum, and the actual one is likely more than 90 times greater.

This study was reviewed by Joseph P. Damore, Jr., M.D., who concluded: “This research is engaging and thoroughly answers the question about the cure being worse than the disease.” Dr. Damore is a certified diplomate with the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University, an assistant attending psychiatrist at New York Presbyterian Hospital, and an adjunct professor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership at the U.S. Military Academy.

Stress and Anxiety Levels

Scientific surveys of U.S. residents have found that the mental health of about one-third to one-half of all adults has been substantially compromised by reactions to the Covid-19 pandemic. Examples include the following:

- An American Psychiatric Association survey in mid-March found that 36% of adults report that anxiety over Covid-19 “is having a serious impact on their mental health.”

- A Kaiser Family Foundation survey in late March found that 45% of adults “feel that worry and stress related to” Covid-19 “has had a negative impact on their mental health, an increase from 32% from early March.” Additionally, 19% of adults said it is having a “major impact” on their mental health.

- A Benenson Strategy Group survey in late March revealed that the Covid-19 “situation has already affected” the “mental health” of 55% of U.S. adults “either a great deal or somewhat.”

- A Kaiser Family Foundation survey in late April found that 56% of adults “report that worry and stress related to” Covid-19 “is affecting their mental health and wellbeing in various ways,” such as “trouble sleeping, “poor appetite or over-eating,” “frequent headaches or stomachaches,” “difficulty controlling their temper,” “increasing their alcohol or drug use,” and “worsening chronic conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure.”

Contributors to these mental health impacts include but are not limited to:

- empirically grounded concerns about the virus.

- anguish over the death of loved ones, although this is limited to a relatively small fraction of the public because the virus has killed one out of every 5,000 Americans, while one out of every 116 Americans die every year.

-

media outlets that overstate the deadliness of Covid-19 by:

- using false denominators that exaggerate its death rate.

- misreporting about the capacity of the virus to mutate and cause a large, ongoing death toll.

-

government stay-at-home orders and self-imposed isolation, as evidenced by:

- a survey commissioned by the University of Phoenix in late March that found 44% of U.S. adults are more lonely than they have ever been in their lives, which is a risk factor for suicide and many other psychologically driven fatal afflictions.

- the late-March Kaiser Family Foundation survey, which “found that 47% of those sheltering in place reported negative mental health effects resulting from worry or stress,” a rate that “is significantly higher than the 37% among people who were not sheltering in place.”

- the late-March Benenson Strategy Group survey, which found that “71% of Americans say they are concerned that ‘social distancing’ measures will have a negative impact on the country’s mental health—including 28% who are extremely or very concerned about this.”

-

government-mandated shutdowns of businesses in nearly every state that have cost millions of jobs and are reflected in the:

- late-April Kaiser Family Foundation survey, which found that 35% of adults and 55% of workers “have lost their jobs or had a reduction in hours or pay as a result of” responses to Covid-19.

- mid-March American Psychiatric Association survey, which found that 57% of adults are concerned that responses to the pandemic “will have a serious negative impact on their finances,” and 68% fear it “will have a long-lasting impact on the economy.”

Among all of the figures above, the lowest nationwide measure of people who have incurred psychological harm from reactions to Covid-19 is the 19% of adults in the late-March Kaiser Family Foundation survey who reported a “major impact” on their mental health. This survey included 1,226 respondents and has a margin of sampling error for this result of ± 2.2 percentage points with 95% confidence.

Therefore, at least 16.8% of 255,200,373 adults in the United States—or 42,873,663 people—have suffered major mental harm from responses to Covid-19. This figure forms the first key basis of this study.

The Deadliness of Anxiety and Stress

Medical journals are rich with studies that attempt to measure the lethality of stress, anxiety, depression, and other psychological conditions. Determining this is very difficult because association does not prove causation, and unmeasured factors could be at play.

For example, a 2011 meta-analysis in the journal Social Science & Medicine about mortality, “psychosocial stress,” and job losses finds that “unemployment is associated with a substantially increased risk of death among broad segments of the population,” but there are conflicting theories as to why this is so. One is that “unemployment causes adverse changes in health behaviors, which in turn lead to deterioration of health.” Put simply, unemployment causes bad health. The other theory is that bad health causes unemployment. Both of these theories may be true, and factors that are not measured in the studies could be causing both unemployment and bad health. Thus, it is very difficult to isolate these variables and determine which is causing the others and to what degree.

While trying to address such uncertainty, the meta-analysis examined “235 mortality risk estimates from 42 studies” and found that “unemployment is associated with a 63% higher risk of mortality in studies controlling for covariates.”

Regardless of whether job losses from Covid-19 lockdowns are brief or sustained, the study found that the death correlation “is significant in both the short and long term,” lending “some support to the hypothesis and previous findings that both the stress and the negative lifestyle effects associated with the onset of unemployment tend to persist even after a person has regained a job.”

Also of relevance to current job losses, the study indicates that added unemployment benefits, like those recently passed into federal law, are unlikely to mitigate the deadliness of job losses. This is because the meta-analysis found that the associations between unemployment and death in Scandinavia and the U.S. are not significantly different, even though the Scandinavian nations offer more generous welfare benefits. Thus, the authors conclude that “these national-level policy differences may not have much of an effect on the rate of mortality following unemployment.”

A broad range of other studies have similar implications for anxiety-related deaths wrought by reactions to Covid-19:

- A 1991 study published by the New England Journal of Medicine found that “psychological stress was associated in a dose-response manner with an increased risk of acute infectious respiratory illness.” A dose-response relationship, as explained by epidemiologist Sydney Pettygrove, “is one in which increasing levels of exposure are associated with either an increasing or a decreasing risk of the outcome.” She notes that when this pattern occurs, it “is considered strong evidence for a causal relationship between the exposure and the outcome.”

- A 2004 paper in The Lancet documents that “stress and depression result in an impairment of the immune response and might promote the initiation and progression of some types of cancer….” The paper details many human and animal studies germane to the Covid-19 lockdowns, such as those dealing with a “lack of social interactions” that cause certain cancers to metastasize.

- A 2005 paper in the Journal of Experimental Medicine finds that “psychological conditions, including stress” trigger a “sophisticated molecular mechanism” that increases “the likelihood of infections, autoimmunity, or cancer.”

- A 2012 meta-analysis in the British Medical Journal finds “a dose-response association between psychological distress and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and external causes across the full range of distress, even in people who would not usually come to the attention of mental health services.” Furthermore, “these associations remained after adjustment for age, sex, current occupational social class, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and diabetes.” People with the lowest levels of psychological distress in this study had a 20% greater risk of death, and those with the highest levels had a 94% greater risk.

-

A 2012 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry analyzes the death rates of more than a million young males in Sweden who underwent a government-mandated military draft physical that “included a structured interview by a psychologist” during 1969 to 1994. This study is particularly relevant to the effects of the current Covid-19 anxiety because it involves nearly all the healthy young men of a nation and excludes those with “severe” mental or physical disorders because they were excused from the exam. The study finds:

- Young men who were diagnosed with neurotic and adjustment disorders were 76% more likely to die in the average follow-up period of 22.6 years. A neurotic disorder is a problem dealing with anxiety, and an adjustment disorder—which is now called “stress response syndrome”—is “a short-term condition that occurs when a person has great difficulty coping with, or adjusting to, a particular source of stress, such as a major life change, loss, or event.” These are apt descriptions of the tens of millions of Americans who report that reactions to Covid-19 are seriously harming their mental health.

- Premature deaths associated with mental illness “are not primarily due to suicide or accidents, although risk of both is increased, but to a range of natural causes, particularly cardiovascular disease.” This suggests that the most pervasive harm from lockdowns does not manifest in obvious ways like suicides and overdoses.

- A 2015 paper in the American Journal of Epidemiology examines the death rates of all “Danes who received a diagnosis of reaction to severe stress or adjustment disorders” between 1995 and 2011. The study found that they “had mortality rates during the study period that were 2.2 times higher than” those of the general population.

-

A 2015 meta-analysis in the Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry provides a systematic review of 148 studies of death and mental disorders with follow-up times ranging from one to 52 years, with a median of 10 years. It finds that the overall risk of death among people with mental disorders is 2.2 times that of the general population. Breaking these results out by condition, the mortality increases were:

- 43% for people with anxiety.

- 71% for people with depression

- 110% for people with mood disorders.

- 150% for people with psychoses.

Among all of the results above, the smallest risk of increased death is 20% in the 2012 meta-analysis. This has a margin of error from 13% to 27% with 95% confidence. The lower limit of 13% translates to an average of about 1.3 years of lost life per person.

Corroborating that figure, 22 of the studies in the 2015 meta-analysis included estimates for the average years of life lost by each person with a mental disorder. These “ranged from 1.4 to 32 years, with a median of 10.1 years.” None of these studies were for anxiety, but the low-end figure of 1.4 years provides additional evidence that those who suffer serious mental repercussions from responses to Covid-19 will lose an average of more than a year of life.

Therefore, the figure of 1.3 years of lost life is a bare minimum and forms the second key basis of this study. This varies widely by person and could be:

- 50 years or more for young people who commit suicide.

- one month or less for elderly persons who have cardiac events triggered by fear or loneliness.

- two years for the middle-aged people whose blood pressure begins spiking earlier in life than it would have in the absence of Covid-19-related stress.

Lives Saved By Lockdowns

In the science of epidemiology, or the study of human disease, ethical and practical constraints often make it impossible to conduct experiments that can definitively establish the effects of medical interventions. This applies to determining how many lives might be saved by government lockdowns during the Covid-19 pandemic.

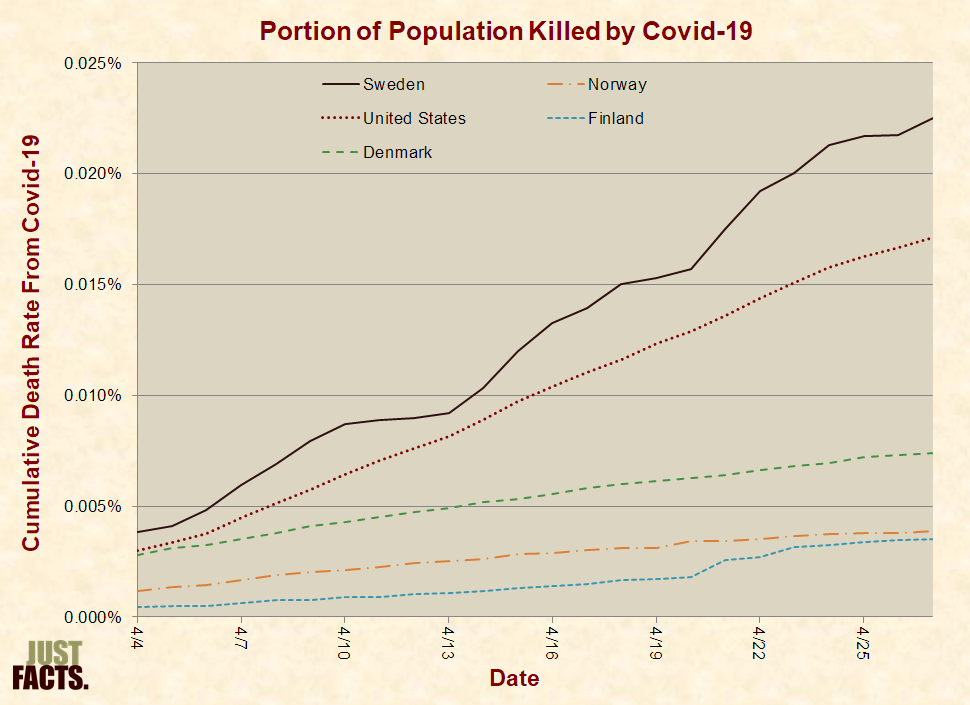

One can easily compare Covid-19 death rates—or the number of people who die from the disease divided by the total population where they live—in nations and states that took different actions. However, many other factors can affect these death rates, such as wealth, age, population density, government, hospital protocols, culture, genetics, diet, and exercise. For example, New York State enacted one of the strictest lockdowns in the U.S. but has 22 times the death rate of Florida, which had one of the mildest lockdowns.

Given such considerations, the highest possible figure for lives saved by lockdowns can be estimated by comparing the nations of Scandinavia. This is because these countries are culturally, economically, and genetically similar to one another but have enacted very dissimilar policies to deal with Covid-19. In the words of Paul W. Franks, professor of genetic epidemiology at Lund University in Sweden:

Sweden has taken certain measures to slow the spread of Covid-19, like limiting public gatherings to 50 people. However, these can hardly be characterized as “lockdowns,” and Swedish stores, restaurants, schools, beaches, and other public places are open and bustling.

Stockholm, Sweden, April 1, 2020 (TT News Agency/Fredrik Sandberg via Reuters)

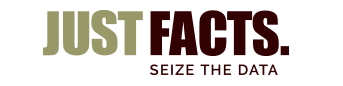

Comparing the current death rates of Scandinavian nations yields a maximum figure for the lives saved by lockdowns because Sweden’s plan involves more deaths in the early stages of the pandemic but less later on. As detailed by Professor Franks, simulations show that the overall death rate is “expected to be similar across countries,” but “unlike its peers, Sweden is likely to take the hit sooner and over a shorter period, with the majority of deaths occurring within weeks, rather than months.”

As of April 27th, the death rate in Sweden is 32% higher than in the United States, 3.1 times that of Denmark, 5.8 times that of Norway, and 6.4 times that of Finland:

Applying the Sweden/Finland death rate ratio of 6.4 to the United States, the maximum number of Americans who could have been saved by past and current lockdowns is 616,590. This figure is based on the most pessimistic projection of 114,228 deaths in the U.S. through August 4th by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. It is calculated by multiplying 114,228 deaths by 6.4 and then subtracting the 114,228 deaths that occur regardless of the lockdown.

The figure of 616,590 lives saved by lockdowns in the U.S. is at the extreme high-end of plausibility because it:

- uses the worst-case projection for the U.S. death toll.

- compares the death rate in Sweden to Finland, even though Denmark—which has also implemented a strict lockdown—has twice the death rate of Finland.

-

assumes that Sweden’s death rate doesn’t decline relative to its neighbors over time regardless of Sweden’s strategy to build herd immunity consistent with the following facts:

- The Imperial College—whose cataclysmic projections of Covid-19 deaths have been a driving force behind government lockdowns—has acknowledged that “the more successful a strategy is at temporary suppression, the larger the later epidemic is predicted to be in the absence of vaccination, due to lesser build-up of herd immunity.”

- A 2012 paper in the journal PLoS One titled “Immunity in Society” notes that “when a sufficiently high proportion of individuals within a population becomes immune (either through prior exposure or through mass vaccination), community or ‘herd’ immunity emerges, whereby individuals that are poorly immunized are protected by the collective ‘immune firewall’ provided by immunized neighbors.”

- Large portions of people are highly resistant to Covid-19 and experience no symptoms when they catch it, later making them firewalls against the spread of the disease. For example, the New England Journal of Medicine reported in mid-April that universal Covid-19 testing of pregnant women at two New York City hospitals found that 88% of the women who tested positive for the disease were asymptomatic.

- U.S. states with strict lockdowns—like New Jersey and New York—have Covid-19 death rates that are three to five times that of Sweden’s:

Nonetheless, this study uses the highly improbable and optimistic scenario of 616,590 lives saved by lockdowns. This figure forms the third key basis of the study.

Comparing Life Lost and Saved

Combining the first two key figures of this study, anxiety from responses to Covid-19 has impacted 42,873,663 adults and will rob them of an average of 1.3 years of life, thus destroying 55.7 million years of life.

Combining the third key figure of this study with data on Covid-19 deaths, a maximum of 616,590 lives might be saved by the current lockdowns, and the disease robs an average of 12 years of life from each of its victims, which means that the current lockdowns can save no more than 7.4 million years of life.

In other words, the anxiety from reactions to Covid-19—such as business shutdowns, stay-at-home orders, media exaggerations, and legitimate concerns about the virus—will extinguish at least seven times more years of life than can possibly be saved by the lockdowns.

Again, all of these figures minimize deaths from anxiety and maximize lives saved by lockdowns. Under the more moderate scenarios documented above, anxiety will destroy more than 90 times the life saved by lockdowns based on:

- the mid-March American Psychiatric Association survey that found Covid-19 “is having a serious impact” on the “mental health” of 36% of adults.

- the 2015 meta-analysis in the Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry that found a 43% average increase in mortality for people with anxiety.

- the IHME’s midpoint projection of 72,433 Covid-19 deaths through August 4th.

- the fact that the current death rate of Sweden is 5.1 times the average of the other Scandinavian nations.

Even the figure of 90 times is likely a substantial underestimate of the total life destroyed by reactions to Covid-19 because it doesn’t account for:

- anyone under the age of 18, even though adolescents are disproportionately prone to stress-related suicides, substance abuse, and risky behaviors that cause fatal accidents.

- deaths caused by low levels of psychological distress—which have impacted an additional 20% of adults beyond the 36% with serious distress according to the late-April Kaiser Family Foundation survey—and are associated with a 20% greater risk of death per the 2012 British Medical Journal meta-analysis.

- psychological conditions that are more deadly than anxiety, like depression and mood disorders. Among the 36% who report a “serious impact” on their “mental health,” there is a mix of conditions, and the 2015 meta-analysis in the Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry finds that the increased risk of death is lowest for anxiety (43%), while it is 71% for depression, and 110% for mood disorders.

-

deaths from non-psychological causes, such as:

- government-mandated and personal decisions to delay medical care, which has postponed tumor removals, cancer screenings, heart surgeries, and treatments for other ailments that can lead to early death if not addressed in a timely manner.

- economic decline and government debt, which have negative effects on healthcare, nutrition, education, and other variables that impact life expectancy.

Unlike analyses that only compare the number of deaths from Covid-19 to other causes, this study accounts for the years of life lost for each victim. This accords with the CDC’s principle that “the allocation of health resources must consider not only the number of deaths by cause but also by age.” Thus, the CDC explains that the “years of potential life lost” has “become a mainstay in the evaluation of the impact of injuries on public health.” This doesn’t mean that the lives of young people are more important than that of the elderly, but it recognizes and accounts for the facts that:

- humans cannot ultimately prevent death; they can only delay it.

- there is a material difference between a malady that kills a 20 year-old in the prime of her life and one that kills a 90-year-old who would have otherwise died a month later.

A possible argument against this study is that it isn’t proper to compare anxiety to Covid-19 because the effects of anxiety often don’t kill until the distant future, while the deaths from Covid-19 are happening right now. Such logic relegates the harms of mental distress to years away, but the facts are clear that it can kill immediately, make life a nightmare in the present, and produce current and lasting physical ailments that end in early death. More importantly, tallying the life lost in any random unit of time, as opposed to an entire lifetime, is shortsighted and exclusionary.

Other distinctions, such as whether or not the cause of death is contagious, are similarly myopic. The primary issues are prevention and harm, and the difference between them ultimately determines how much life is saved or destroyed.

Summary

One of the most important principles of epidemiology is weighing benefits and harms. A failure to do this can make virtually any medical treatment seem helpful or destructive. In the words of Ronald C. Kessler of the Harvard Medical School and healthcare economist Paul E. Greenberg, “medical interventions are appropriate only if their expected benefits clearly exceed the sum of their direct costs and their expected risks.”

Likewise, a 2020 paper about quarantines published in The Lancet states: “Separation from loved ones, the loss of freedom, uncertainty over disease status, and boredom can, on occasion, create dramatic effects. Suicide has been reported, substantial anger generated, and lawsuits brought following the imposition of quarantine in previous outbreaks. The potential benefits of mandatory mass quarantine need to be weighed carefully against the possible psychological costs.”

Yet, when dealing with Covid-19 and other issues, politicians sometimes ignore this essential principle of sound decision-making. For a prime example, NJ Governor Phil Murphy recently insisted that he must maintain a lockdown or “there will be blood on our hands.” What that statement fails to recognize is that lockdowns also kill people via the mechanisms detailed above.

Likewise, a reporter asked NY Governor Andrew Cuomo about the impacts of his lockdown on people who commit “suicide because they can’t pay their bills” and others who die from the economic repercussions and “mental illness.” In reply, Cuomo stated five times that these fatal outcomes are “not death.” He also asked the rhetorical question, “How can the cure be worse than the illness if the illness is potential death?” The obvious answer is that the cure is also potential death.

In situations like pandemics and many other realms of public policy, life-and-death tradeoffs are inevitable, and failing to recognize this can cause tremendous harm. This is the case with Covid-19, where a broad array of scientific facts overwhelmingly shows that anxiety from reactions to the disease will destroy at least seven times more years of life than can possibly be saved by lockdowns. Moreover, the total loss of life from all societal responses to this disease is likely to be more than 90 times greater than prevented by the lockdowns.

A final note for readers who are experiencing anxiety: Healthcare professionals can reduce these effects, so seek help.

Dr. Andrew Glen is a Professor Emeritus of Operations Research from the United States Military Academy. He is a thirty-year U.S. Army veteran and an award-winning researcher in the field of computational probability.

James D. Agresti is the president of Just Facts, a think tank dedicated to publishing rigorously documented facts about public policy issues.